| Roy Lichtenstein | |

|---|---|

Roy Lichtenstein, 1985 | |

| Birth name | Roy Fox Lichtenstein[1] |

| Born | October 27, 1923 Manhattan, New York, U.S. |

| Died | September 29, 1997 (aged 73) Manhattan, New York, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Field | Painting, Sculpture |

| Training | Ohio State University |

| Movement | Pop Art |

Roy Lichtenstein (October 27, 1923 – September 29, 1997) was a prominent American pop artist. During the 1960s his paintings were exhibited at the Leo Castelli Gallery in New York City and along with Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, James Rosenquist and others he became a leading figure in the new art movement. His work defined the basic premise of pop art better than any other through parody. [2] Favoring the old-fashioned comic strip as subject matter, Lichtenstein produced hard-edged, precise compositions that documented while it parodied often in a tongue-in-cheek humorous manner. His work was heavily influenced by both popular advertising and the comic book style. He himself described Pop Art as, "not 'American' painting but actually industrial painting".[3]

Contents[hide] |

[edit] Early years

Roy Lichtenstein was born in Manhattan into an upper-middle-class New York City[1] family and attended public school until the age of 12. He then enrolled at Manhattan's Franklin School for Boys, remaining there for his secondary education.[1] Art was not included in the school's curriculum; Lichtenstein first became interested in art and design as a hobby.[4] He was an avid jazz fan, often attending concerts at the Apollo Theater in Harlem.[4] He frequently drew portraits of the musicians playing their instruments.[4] After graduation from Franklin, Lichtenstein enrolled in summer classes at the Art Students League of New York, where he worked under the tutelage of Reginald Marsh.[3]

Lichtenstein then left New York to study at the Ohio State University, which offered studio courses and a degree in fine arts.[1] His studies were interrupted by a three-year stint in the army during and after World War II between 1943 and 1946.[1] Lichtenstein returned home to visit his dying father and was discharged from the army under the G.I. Bill.[4] He returned to studies in Ohio under the supervision of one of his teachers, Hoyt L. Sherman, who is widely regarded to have had a significant impact on his future work (Lichtenstein would later name a new studio he funded at OSU as the Hoyt L. Sherman Studio Art Center).[5] Lichtenstein entered the graduate program at Ohio State and was hired as an art instructor, a post he held on and off for the next ten years. In 1949 Lichtenstein received a M.F.A. degree from the Ohio State University and in the same year married Isabel Wilson who was previously married to Ohio artist Michael Sarisky (Isabel divorced Roy Lichtenstein in 1965).[6] In 1951 Lichtenstein had his first one-man exhibition at the Carlebach Gallery in New York.[1][7]

He moved to Cleveland in the same year, where he remained for six years, although he frequently travelled back to New York. During this time he undertook jobs as varied as a draftsman to a window decorator in between periods of painting.[1] His work at this time fluctuated between Cubism and Expressionism.[4] In 1954 his first son, David Hoyt Lichtenstein, now a songwriter, was born. He then had his second son, Mitchell Lichtenstein in 1956.[3] In 1957 he moved back to upstate New York and began teaching again.[3] It was at this time that he adopted the Abstract Expressionism style, a late convert to this style of painting.[4] From 1970 until his death, Lichtenstein split his time between New York city and a house near the beach in Southampton.[8]

[edit] Rise to fame

Lichtenstein began teaching in upstate New York at the State University of New York at Oswego in 1958. However, the brutal upstate winters were taking a toll on him and his wife.[9]

In 1960, he started teaching at Rutgers University where he was heavily influenced by Allan Kaprow, who was also a teacher at the University. This environment helped reignite his interest in Proto-pop imagery.[1] In 1961 Lichtenstein began his first pop paintings using cartoon images and techniques derived from the appearance of commercial printing. This phase would continue to 1965, and included the use of advertising imagery suggesting consumerism and homemaking.[4] His first work to feature the large-scale use of hard-edged figures and Ben-Day dots was Look Mickey (1961, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.).[6] This piece came from a challenge from one of his sons, who pointed to a Mickey Mouse comic book and said; "I bet you can't paint as good as that, eh, Dad?"[10] In the same year he produced six other works with recognizable characters from gum wrappers and cartoons.[11] In 1961 Leo Castelli started displaying Lichtenstein's work at his gallery in New York. Lichtenstein had his first one-man show at the Castelli gallery in 1962; the entire collection was bought by influential collectors before the show even opened.[1] In September 1963 he took a leave of absence from his teaching position at Douglass College at Rutgers.[12]

[edit] Fame

It was at this time, that Lichtenstein began to find fame not just in America but worldwide. He moved back to New York to be at the center of the art scene and resigned from Rutgers University in 1964 to concentrate on his painting.[4] Lichtenstein used oil and Magna paint in his best known works, such as Drowning Girl (1963), which was appropriated from the lead story in DC Comics' Secret Hearts #83. (Drowning Girl now hangs in the Museum of Modern Art, New York.[4]) Also featuring thick outlines, bold colors and Ben-Day dots to represent certain colors, as if created by photographic reproduction. Lichtenstein would say of his own work: Abstract Expressionists "put things down on the canvas and responded to what they had done, to the color positions and sizes. My style looks completely different, but the nature of putting down lines pretty much is the same; mine just don't come out looking calligraphic, like Pollock's or Kline's."[13]

Rather than attempt to reproduce his subjects, his work tackled the way mass media portrays them. Lichtenstein would never take himself too seriously however: "I think my work is different from comic strips- but I wouldn't call it transformation; I don't think that whatever is meant by it is important to art".[3] When his work was first released, many art critics of the time challenged its originality. More often than not they were making no attempt to be positive. Lichtenstein responded to such claims by offering responses such as the following: "The closer my work is to the original, the more threatening and critical the content. However, my work is entirely transformed in that my purpose and perception are entirely different. I think my paintings are critically transformed, but it would be difficult to prove it by any rational line of argument".[3]

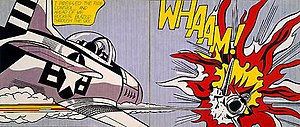

His most famous image is arguably Whaam! (1963, Tate Modern, London[14]), one of the earliest known examples of pop art, adapted a comic-book panel from a 1962 issue of DC Comics' All-American Men of War.[15] The painting depicts a fighter aircraft firing a rocket into an enemy plane, with a red-and-yellow explosion. The cartoon style is heightened by the use of the onomatopoeic lettering "Whaam!" and the boxed caption "I pressed the fire control... and ahead of me rockets blazed through the sky..." This diptych is large in scale, measuring 1.7 x 4.0 m (5 ft 7 in x 13 ft 4 in).[14]

Most of his best-known artworks are relatively close, but not exact, copies of comic book panels, a subject he largely abandoned in 1965. (He would occasionally incorporate comics into his work in different ways in later decades.) These panels were originally drawn by such comics artists as Jack Kirby and DC Comics artists Russ Heath, Tony Abruzzo, Irv Novick, and Jerry Grandenetti, who rarely received any credit. Jack Cowart, executive director of the Lichtenstein Foundation, contests the notion that Lichtenstein was a copyist, saying: "Roy's work was a wonderment of the graphic formulae and the codification of sentiment that had been worked out by others. The panels were changed in scale, color, treatment, and in their implications. There is no exact copy."[16] However, some[17] have been critical of Lichtenstein's use of comic-book imagery, especially insofar as that use has been seen as endorsement of a patronizing view of comic by the art mainstream;[17] noted comics author Art Spiegelman commented that "Lichtenstein did no more or less for comics than Andy Warhol did for soup."[17]

In 1967, his first museum retrospective exhibition was held at the Pasadena Art Museum in California. Also in this year, his first solo exhibition in Europe was held at museums in Amsterdam, London, Bern and Hannover.[6] He married his second wife, Dorothy Herzka in 1968.[6]

In the 1970s and 1980s, his style began to loosen and he expanded on what he had done before. He produced a series of "Artists Studios" which incorporated elements of his previous work. A notable example being Artist's Studio, Look Mickey (1973, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis) which incorporates five other previous works, fitted into the scene.[1]

In the late 1970s, this style was replaced with more surreal works such as Pow Wow (1979, Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst, Aachen).

In 1977, he was commissioned by BMW to paint a Group 5 Racing Version of the BMW 320i for the third installment in the BMW Art Car Project.

In addition to paintings, he also made sculptures in metal and plastic including some notable public sculptures such as Lamp in St. Mary’s, Georgia in 1978, and over 300 prints, mostly in screenprinting.[18]

His painting Torpedo...Los! sold at Christie's for $5.5 million in 1989, a record sum at the time, making him one of only three living artists to have attracted such huge sums.[6]

In 1996 the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. became the largest single repository of the artist's work when he donated 154 prints and 2 books. In total there are some 4,500 works thought to be in circulation.[1]

He died of pneumonia in 1997[10] at New York University Medical Center.

He was survived by his second wife, Dorothy, and by his sons, David and Mitchell, from his first marriage. The DreamWorks Records logo was his last completed project.[1]

His work Crying Girl was one of the artworks brought to life in Night at the Museum: Battle of the Smithsonian.

[edit] Relevance

Pop art continues to influence the 21st century. Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol were used in U2's 1997, 1998 PopMart Tour and in an exhibition in 2007 at the British National Portrait Gallery.

Among many other works of art destroyed in the World Trade Center attacks on September 11, 2001, a painting from Roy Lichtenstein’s The Entablature Series was destroyed in the fire.[19]

[edit] Awards

- 1995 National Medal of the Arts, Washington D.C.

- 1995 Kyoto Prize, Inamori Foundation, Kyoto, Japan.

- 1993 Amici de Barcelona, from Mayor Pasqual Maragall, L’Alcalde de Barcelona.

- 1991 Creative Arts Award in Painting, Brandeis University, Waltham, Massachusetts.

- 1989 American Academy in Rome, Rome, Italy. Artist in residence.

- 1979 American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York.

- 1977 Skowhegan Medal for Painting, Skowhegan School, Skowhegan, Maine.

[edit] References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Clare Bell. "The Roy Lichtenstein Foundation - Chronology". http://www.lichtensteinfoundation.org/lfchron1.htm. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

- ^ Arnason, H., History of Modern Art: Painting, Sculpture, Architecture, New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. 1968.

- ^ a b c d e f Coplans, John (1972). Roy Lichtenstein. Interviews, p55, 30, 31.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hendrickson, Janis (1993). Lichtenstein. pp. 94.

- ^ The Ohio State University. "Sculpture. Facilities". http://art.osu.edu/?p=ds_facilities. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

- ^ a b c d e Alloway, Lawrence (1983). Roy Lichtenstein. pp. 113.

- ^ Clare Bell. "Roy Lichtenstein Exhibitions..... 1946-2009". http://www.lichtensteinfoundation.org/solexint.htm. Retrieved 2009-12-08.

- ^ Julianelli, Jane (1997-02-02). "Actor Finds That His Roles Walk on the Darker Side of Life". New York Times. http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F10F10F93C590C718CDDAB0894DF494D81.

- ^ Gayford, Martin (2004-02-25). "Whaam! Suddenly Roy was the darling of the art world". The Daily Telegraph (London). http://www.telegraph.co.uk/arts/main.jhtml?xml=/arts/2004/02/25/baroy23.xml. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

- ^ a b Lucie-Smith, Edward (September 1, 1999). Lives of the Great 20th-Century Artists. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0500237397.

- ^ Lobel, Michael (2002). Image Duplicator. pp. 33.

- ^ Joan M Marter, Off limits: Rutgers University and the Avant-Garde 1957-1963, Rutgers University Press, 1999, p37. ISBN 0-8135-2610-8

- ^ Kimmelman, Michael (1997-09-30). "Roy Lichtenstein, Pop Master, Dies at 73". New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9B03E0DF103AF933A0575AC0A961958260&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=3. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

- ^ a b Lichtenstein, Roy. "Whaam!". Tate Collection. http://www.tate.org.uk/servlet/ViewWork?workid=8782. Retrieved 2008-01-27.

- ^ Lichtenstein, Roy. "Whaam!". Roy Lichtenstein Foundation website. http://www.image-duplicator.com/main.php?decade=60&year=63&work_id=137. Retrieved 2009-09-12.

- ^ Beam, Alex (October 18, 2006). "Lichtenstein: creator or copycat?" (Web). Editorial. Boston.com. http://www.boston.com/news/globe/living/articles/2006/10/18/lichtenstein_creator_or_copycat/. Retrieved 2007-07-16.

- ^ a b c Sanderson, Peter. "Art Spiegelman Goes to College". Publishers Weekly. http://www.publishersweekly.com/article/406197-Spiegelman_Goes_to_College.php. Retrieved 2010-03-26.

- ^ Corlett, Mary Lee. The prints of Roy Lichtenstein, a catalogue raisonné, 1948-1997 2nd ed. (New York: Hudson Hills Press, 2002).

- ^ Kelly Devine Thomas (November 2001). "Aftershocks". ARTnews. http://www.artnews.com/issues/article.asp?art_id=1005. Retrieved 2008-09-13.

[edit] Further reading

- Roy Lichtenstein by Janis Hendrickson - ISBN 3-8228-0281-6

- The Prints of Roy Lichtenstein: A Catalogue Raisonné 1948-1997 by Mary L. Corlett - ISBN 1-55595-196-1

- Roy Lichtenstein (Modern Masters Series, Vol. 1) by Lawrence Alloway - ISBN 0-89659-331-2

- Roy Lichtenstein Interview with Chris Hunt Image Entertainment video, 1991

- Roy Lichtenstein Interview with Melvyn Bragg video

- Off Limits: Rutgers University and the Avant-Garde, 1957-1963 - Ed. Joan Marter - ISBN 0-8135-2609-4

- Roy Lichtenstein's ABC's by Bob Adelman - ISBN 978-0-8212-2591-2

- Roy Lichtenstein Drawings and Prints 1970 Chelsea House publishers, introduction by Diane Waldman

[edit] External links

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Roy Lichtenstein |

- Roy Lichtenstein Foundation

- Roy Lichtenstein Image Duplicator

- The Art Archive: Roy Lichtenstein

- Deconstructing Roy Lichtenstein (sources for Lichtenstein's comic-book paintings)

- Inside Roy Lichtenstein's Studio 1990-92

- Roy Lichtenstein at Find a Grave

- Roy Lichtenstein - slideshow by The New York Times

- 1977 BMW 320i with special paintjob by Roy Lichtenstein

- Roy Lichtenstein's public artwork at Times Square-42nd Street, commissioned by MTA Arts for Transit.